LA VIA CHE PORTA IN ALTO E QUELLA CHE PORTA IN BASSO

SONO LA STESSA IDENTICA VIA (Eraclito)

Il termine “Occidente” nasconde un equivoco pesante.

Nell’anno 2008, non si è più agli inizi del secolo XX, quando ancora uno Spengler (nella foto in basso) poteva parlare della crisi dell’Occidente come fase terminale di un’involuzione ciclica mondiale. O un Massis poteva invocare la défense de l’Occident.

O un Massis poteva invocare la défense de l’Occident.

Oggi non c’è più alcun Occidente da difendere, ma ce n’è uno da cui difendersi.In questi cento anni, la nostra civiltà ha visto bruciare la sua ultima grande possibilità, quella profetizzata appunto da Spengler come fase faustiana, cesaristica, che in un ultimo sforzo di interiore potenza sarebbe sorta dal ventre europeo come antidoto alla sincope finale della civiltà dell’uomo bianco, causata dal progressismo.

Alla metà del Novecento, al culmine di una crisi comatosa mondiale risolta dalla violenza bruta, si è potuto assistere allo strangolamento nella culla proprio di questo ciclo storico faustiano appena insorto, che il filosofo tedesco aveva vaticinato in qualità di ultima e conclusiva manifestazione creativa dell’anima europea. Tale crimine è stato consumato precisamente per mano di un’appendice occidentale, non-europea e anzi anti-europea. La mano che ha soppresso l’Europa in quanto civiltà espressiva e centro di potere individuato, proveniva da Occidente.

Quest’appendice, che ha impedito al nostro continente di riappropriarsi sul ciglio dell’abisso del suo destino e del suo spirito – secondo vie che forse avrebbero soltanto dilazionato il tracollo, ma probabilmente di secoli – ha rappresentato, sin dal suo primo formarsi nel secolo XVIII, una precisa congiura contro l’Europa e tutti i suoi patrimoni culturali, che dalle profondità della protostoria erano giunti sostanzialmente impregiudicati fino nel cuore dell’età contemporanea.

Parliamo infatti dell’America, di quel bacino di formidabili energie distruttive infuse nel calderone progressista, giunte a maturazione utilizzando i letali ingredienti del puritanesimo, del biblismo, del liberismo e del materialismo capitalista: dalla micidiale mistura è uscito un cocktail infernale che, fatto bere a forza ai popoli europei dopo il 1945, ne ha garantita la rapida liquidazione come entità culturali e politiche storicamente individuate.

Quello che è nel frattempo avvenuto è stato infatti il tramonto dell’Europa e l’insediarsi in suo luogo dell’Occidente made in USA. L’Occidente, nel senso geografico e politico di America, è ciò che è uscito in qualit à di solo vincitore dalla lotta tra l’onore dell’appartenenza, valore di fondazione senza il quale i nostri popoli non avrebbero potuto darsi una forma, e il disonore della disgregazione affidata al culto totemico del denaro e dell’individualismo di massa.

à di solo vincitore dalla lotta tra l’onore dell’appartenenza, valore di fondazione senza il quale i nostri popoli non avrebbero potuto darsi una forma, e il disonore della disgregazione affidata al culto totemico del denaro e dell’individualismo di massa.

Chi confonde l’Europa con l’Occidente, cioè con ciò che oggi coincide con l’America, non ha compreso il dramma della civiltà bianca. Chi giudica l’Europa e l’America come un’unica civilizzazione accomunata da comuni linguaggi esistenziali e da una comune volontà di destino, mostra di non avere la sensibilità che occorre per distinguere la creatività dalla distruzione, l’ordine dal caos, l’ideale dal materiale, il sano dal malato, il bello dal brutto.

Si tratta di due antitesi, di due antropologie, di due monadi.

Oggi l’Europa è in coma perché sottoposta alle radiazioni americane. Il vampirismo si è ormai compiuto, e nuove costellazioni extra-europee e anche extra-occidentali già sorgono all’orizzonte, preparando una sicura fase di regolamenti di conti con gli stessi Stati Uniti, un colosso vacillante che, se privato della forza materiale, rappresenta un vuoto inespressivo tutto sommato molto fragile.

Scriveva Georges Bernanos nel 1947 che

«l’Europa è tramontata nel momento stesso in cui ha dubitato di sé, della sua vocazione e del suo diritto […] e questo momento ha coinciso con l’avvento del capitalismo totalitario», sancendo in questo modo proprio la vittoria del denaro contro l’onore.

Ma chi mise nel cuore europeo il tarlo roditore del dubbio di sé, cosa minò l’antico senso europeo della sua vocazione e del suo diritto in faccia al mondo? Non furono proprio l’ideologia dei diritti individuali e quella del capitalismo calvinista, non furono l’illuminismo e il razionalismo sposati al liberismo inglese, al biblismo millenarista delle sette protestanti che, una volta lasciati fermentare nello spazio del Nuovo Mondo, produssero l’odio per la tradizione europea, la diffamazione del nostro passato, l’incomprensione per la nostra storia e per le nostre realizzazioni sociali?

Quest’informe viluppo di nevrosi sotto maschera moderna, costituito dai riformatori fondamentalisti, fino a quando rimase un caso clinico di minoranze europee ben controllate e circoscritte dal discredito generale (le allucinazioni anabattiste, i deliri di un Giovanni di Leyda circa il “Regno di Dio” in terra, le psicosi settarie dei profetismi biblici, il concetto di capitale usurario come fonte di benedizione divina…) non costituirono alcun pericolo reale per i popoli europei. Episodi marginali, di cui furono in molti allora a non accorgersi neppure.

Ma quando tutta questa schiuma di allucinati e di malati mentali, di invasati di versetti biblici, insieme ai tagliagola, ai criminali e agli asociali fuggiti da tutta Europa, prese a sbarcare a frotte sulle coste americane, là dove non c’era l’Europa con la sua cultura a fare da involucro, proprio in quel momento il destino europeo si compì.

Ci vollero due-tre secoli di gestazione, ma poi la risacca, montata in uno spazio reso deserto dall’etnocidio dei nativi americani e ripopolato con lo schiavismo e il fuoriscitismo dei peggiori elementi espulsi dai popoli europei, è ritornata da noi come un pendolo dannato, sotto l’etichetta di “ideologia americana”. Qualcosa che è stato sin dall’inizio ben deciso a fare a pezzi ciò che era rimasto della vecchia Europa. I lugubri “padri pellegrini” sono tornati di qua dell’Atlantico come un turbine di sventura, hanno riportato indietro con sé il dono avvelenato delle loro distorsioni mentali, ma potenziate in ideologia di potere mondiale, e in più sorrette da una potenza industriale mai prima vista.

Quelli che erano poveri alienati nel Seicento, nel Novecento si sono potuti presentare ai popoli europei addirittura come i “liberatori”, i portatori del “benessere”, i garanti di una “nuova frontiera” di riscatto materiale e morale. Lo sguardo alienato, quelle occhiaie da invasato febbricitante di visioni veterotestamentarie che ebbe ad esempio un Lincoln (un uomo con problemi di disagio mentale acclarato: riferiscono i biografi che fosse una specie di semidemente lombrosiano, che non mancò di suscitare perplessità nei suoi stessi contemporanei), ha potuto diventare una faccia da “liberatore”.

L’icona, il marchio stesso dell’America.

Al di sotto di Hollywood e di Mc Donald’s corre un fiume di tetra e morbosa volontà rieducatoria, quelle tirate quacchere sul destino di dominio del mondo in nome di Jeovah, quel maledire la diversità, quel sentirsi “eletti” alla salvezza…un’anima fobica e contorta, tutta avvolta dalla sindrome di rappresentare il bene e pertanto di poter infliggere agli altri il male. È la fiaba del lupo travestito da agnello. È quello sbaglio della storia che si chiama Stati Uniti.

Nel Novecento non sono stati più i pochi disadattati del Seicento a straparlare di Nuova Israele nella penombra di qualche taverna massonica del New England: stavolta era una potenza mondiale, era la modernità in persona, un’organizzazione formidabile, risoluta a volgere le elucubrazioni dei padri predicatori evangelisti in un lucido progetto di dominazione universale.

Con i mezzi dell’etnocidio metodico prima e dell’annientamento coscienziale propagandistico poi, col metodo mai smesso del ricatto e dell’intimidazione, è stato strappato all’Europa il diritto di essere se stessa, relegandola al rango di provincia cui imporre liberamente i propri voleri. L’Occidente ha minato alle fondamenta il diritto dell’Europa a rimanere fedele ai propri simboli, salda al suo posto, come andava facendo da un paio di millenni.

In questo quadro, cosa può ancora significare volgere lo sguardo a ciò che l’Europa è stata nei secoli?

Cosa può ancora dire ai popoli europei di oggi il richiamo alle loro tradizioni di ineguagliata cultura, ai loro primati di sapere e di volere, ai loro fondamenti di identità e di legame?

Ha ancora un senso parlare di civiltà europea, dato che possiamo solo riferirci a un passato che è stato rinnegato e irriso dai nuovi dominatori occidentali, col consenso prima estorto e poi spontaneo delle nostre élites culturali e delle masse? Esprimere la parola di verità nel dominio totale della confusione e dell’invertimento dei significati è operazione probabilmente inutile. Ma proprio per questo va ugualmente tentata.

La lotta novecentesca, a cui l’Europa non è sopravvissuta, è stata essenzialmente una lotta tra l’Ordine e il disordine.

Un mondo di forme e proporzioni è crollato dinanzi alla violenta intrusione di un mondo di difformità e asimmetrie. Tra i documenti più antichi della nostra civiltà, è stato da molto tempo notato in posizione di pietra d’angolo il concetto di Ordine.

Ben oltre l’Illuminismo o il Cristianesimo, che si vorrebbero a fondamento dell’Occidente-Europa (da parte di quanti non avvertono l’ingiuria di unificare i due opposti), e anche oltre il mondo classico, noi troviamo il mondo indoeuropeo: qui l’Europa, piuttosto che dell’Occidente, è sposa feconda dell’Oriente.

Indoeuropeismo significa soprattutto verifica che l’Origine è sorta insieme al senso dell’ordinamento, della percezione sensibile della misura e della conformazione al creato. In questi ambiti, il popolo vive la sostanza intima della natura, ne ripete nella socialità gli schemi di complementarietà dei ruoli, non va in cerca di soluzioni astratte, ma vive concretamente nella dimensione di una realtà visibile, cosmica come umana.

Non altrimenti, se non come rispecchiamenti dell’ordine naturale, possono essere giudicati i nostri più antichi documenti identitari, quali i Veda o le Upanishad, che vivono ancora oggi nei vocabolari e nelle lingue delle culture europee.

Notava non a caso Adriano Romualdi che nell’inno vedico a Mithra e Varuna (un millennio e mezzo prima di Cristo) si impetravano le energie ordinatrici del cosmo, quali archetipi sul cui metro dare compimento alle edificazioni sociali umane. Tutto è dipeso e ha preso vita inizialmente da questa mattinale consapevolezza che all’uomo non è dato sottrarsi alla sua natura e alle leggi del mondo nel quale si trova “gettato”. Il paganesimo arcaico e quello classico non fecero che ratificare questo dato di fatto.

La sorgente della civiltà europea sgorgò dall’intuizione della presenza dell’Ordine, ovunque e in tutte le cose. C’è sempre una legge che stabilisce i nessi, che dà un limite, che indica un “fin qui e non oltre”. C’è sempre una necessità che regola i rapporti tra le cose, gli uomini e gli eventi. Se ne avessimo lo spazio, sarebbe facile ammassare le prove culturali occorrenti a dimostrare che il sorgere della nostra civiltà – sin nell’esatta rispondenza etimologica tra il rito religioso e politico e l’ordine cosmico – si radica nella legge delle gerarchie e delle aggregazioni tra simili, quali sono presenti in natura.

Basterà un piccolo esempio.

A un certo punto, nella Repubblica di Platone si parla di due vie: quella che trascina verso il basso e quella che conduce verso l’alto. Platone racconta che la prima è quella battuta da Socrate, allorquando un giorno, per assistere a una festa, scende lungo la strada che porta da Atene, su in alto, al Pireo, giù in basso. Qui al porto, simbolo di mercanteggiamento, di confusione di genti e di caos, ciò che regna è il formicolare dei cittadini e dei forestieri, che in casuale e disordinata comunanza perdono ogni sigillo di nobiltà differenziante.

È il luogo per eccellenza della mescolanza e dell’infrazione, è lo spazio dell’eccezione, in cui vigono il frammisto e l’incomposto, simboleggiati dai riti stranieri in cui tutti sono uguali.

Qui, l’Io identitario è a repentaglio, è il kateben, il discendere che esprime l’avventurarsi nell’alieno e nel difforme, paragonato all’Ade, alla perdizione coscienziale, addirittura alla morte. Dopo la festa, Socrate, sensibile al richiamo di ritornare al più presto nel seno della propria polis, si affretta a rientrare in città, a risalire lassù nella sua città, nello scrigno della sua comunità, lungo la via che riconduce in alto, al proprio, al simile e al composto, vincendo le insistenze di certi amici che vorrebbero trattenerlo.

È questo il racconto allegorico della discesa pericolosa nell’Altro-da-sé, è la simbologia platonica in cui si racconta l’appartenenza politica e filosofica alla polis come vicenda di pericoli da vincere e tentazioni da attraversare con salda tenuta.

Essa è parallela al mito di Er, il figlio di Panfilia (“l’amica di tutti”, l’indifferenziata), anch’esso metafora di caduta nella perdizione.

Eric Voegelin, nel commentare questi passi della Repubblica, nel suo libro Ordine e storia precisò in maniera oltremodo eloquente che si trattava di un tema irto di simboli. Al cui epicentro si trovava la celebrazione dell’Ordine, quale categoria politica e umana giudicata insostituibile. Il “panfilismo” del Pireo – ha scritto Voegelin –, il suo essere luogo egualitario e livellante, dove ognuno è uguale a tutti gli altri, lo rende simile all’Ade, alla morte: «è il “panfilismo” del Pireo che lo rende Ade. L’eguaglianza del porto è la morte di Atene».

La via che discende, là dove i limiti si frantumano e le differenze si annullano, comporta dunque il precipitare nella morte di Atene. Poiché Atene muore quando muore nel cuore dei suoi cittadini.

Lo stesso significato è presente nella figura del ricco Cefalo, un vecchio incontrato da Socrate, col cui personaggio Platone vuol significare la crisi epocale, la renitenza di una generazione indebolita dinanzi ai valori, la trascuratezza della legge.

E, anche in questo caso, il simbolo platonico torna a parlare con evidenza:

«Di colpo diviene manifesto – commentava Voegelin a proposito di questo episodio – che la vecchia generazione ha trascurato di costruire la sostanza dell’ordine nei giovani e un’amabile indifferenza, unita a una certa confusione, si trasforma in pochi anni negli orrori della catastrofe sociale».

Non è possibile seguire oltre questi temi, che sarebbe interessante sviluppare fino in fondo. Ma si sarà capito lo stesso, dai pochi cenni fatti, che è proprio l’Ordine – naturale, interiore, umano, sociale, politico – il nervo sensibile che fu avvertito dalla nostra cultura antica come quello decisivo per assicurare alla Città la sua fortuna, se mantenuto; la sua rovina, se tradito.

Ora, di fronte a questo ancestrale sentimento prima indoeuropeo, poi ellenico, romano, gotico (si pensi ad es. ai significati di ordinamento cosmico che avevano sia i collegia romani che le corporazioni medievali), si erge il colosso distruttivo del dis-ordine applicato a tutti campi (politico, familiare, sociale, mentale, economico), concepito e realizzato alla fine in America in simultanea con l’idea di mercato liberista.

Che è considerato come sinonimo di “libertà” perché aperto e senza limiti, in perenne espansione, disumano, annullando con ciò dalle fondamenta il concetto rigoroso di Ordine e di misura.

Che è innanzi tutto un principio regolatore, un demarcatore, e quindi un discriminatore che fissa leggi, che qui ingloba e là per forza esclude, disponendo frontiere e sbarramenti precisi, logici, ideali come materiali, senza i quali si entra nell’illimite e nel privo di senso, il regno del caos.

La finale perdita europea dell’onore che è legato all’applicazione dell’Ordine in ogni manifestazione della vita, dopo le iniziali aggressioni del Cristianesimo paolino, dell’Illuminismo e del marxismo, la dobbiamo all’egemonia del pensiero americano di derivazione puritano-utilitarista, incardinato sulla menzognera divulgazione di un’idea di “libertà” che coincide con l’annientamento della personalità individuale e sociale.

La disintegrazione di ciò che Spengler chiamava ancora “Occidente” data da quando l’America ha distrutto le fondamenta della Tradizione europea, sostituendo ad esse la patologia settaria del totalitarismo capitalista e millenarista. Da un pezzo l’Occidente non parla più con la voce solenne di Platone, ma con quella stridula dei miliardari anabattisti americani travestiti da capi politici.

Luca Leonello Rimbotti

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

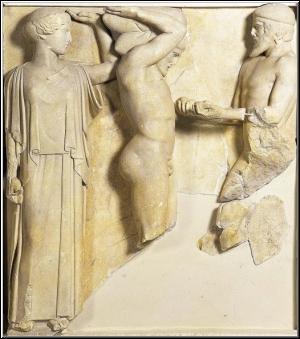

Each High Culture has as a distinguishing feature a "prime symbol." The Egyptian symbol, for example, was the "Way" or "Path," which can be seen in the ancient Egyptians' preoccupation -- in religion, art, and architecture (the pyramids) -- with the sequential passages of the soul. The prime symbol of the Classical culture was the "point-present" concern, that is, the fascination with the nearby, the small, the "space" of immediate and logical visibility: note here Euclidean geometry, the two-dimensional style of Classical painting and relief-sculpture (you will never see a vanishing point in the background, that is, where there is a background at all), and especially: the lack of facial expression of Grecian busts and statues, signifying nothing behind or beyond the outward. [Image: Atlas Bringing Heracles the Golden Apples in the presence of Athena, a metope illustrating Heracles' Eleventh Labor, with Athena helping Heracles hold up the sky. From the Temple of Zeus in Olympia, c. 460 BC.]

Each High Culture has as a distinguishing feature a "prime symbol." The Egyptian symbol, for example, was the "Way" or "Path," which can be seen in the ancient Egyptians' preoccupation -- in religion, art, and architecture (the pyramids) -- with the sequential passages of the soul. The prime symbol of the Classical culture was the "point-present" concern, that is, the fascination with the nearby, the small, the "space" of immediate and logical visibility: note here Euclidean geometry, the two-dimensional style of Classical painting and relief-sculpture (you will never see a vanishing point in the background, that is, where there is a background at all), and especially: the lack of facial expression of Grecian busts and statues, signifying nothing behind or beyond the outward. [Image: Atlas Bringing Heracles the Golden Apples in the presence of Athena, a metope illustrating Heracles' Eleventh Labor, with Athena helping Heracles hold up the sky. From the Temple of Zeus in Olympia, c. 460 BC.]